For the pdf slides, click here

Matching

Experiments vs observational studies

Randomized trials

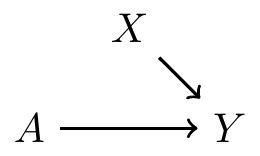

In experiments, treatment is determined by a coin toss; so there are no arrows from to , i.e., no backdoor paths

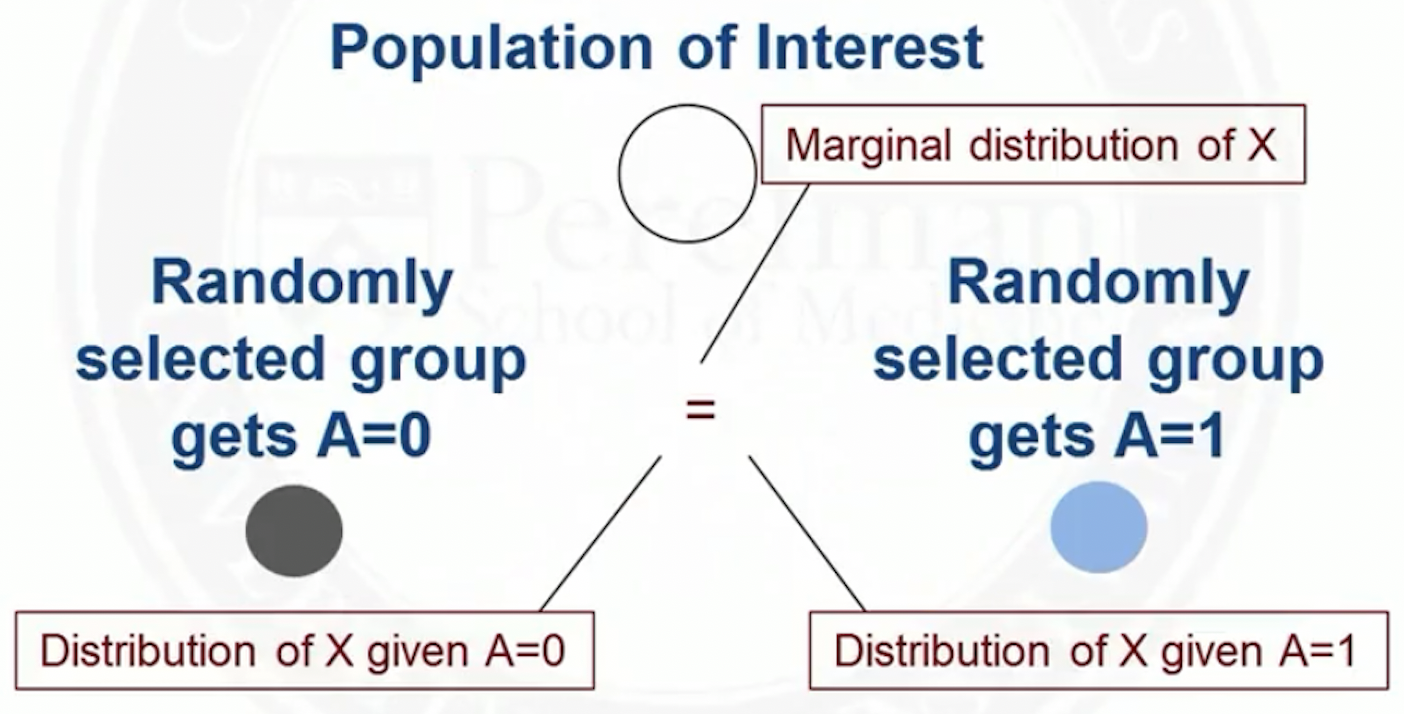

Covariate balance: distribution of pre-treatment variables are the same in both treatment groups

- Hence, if there is difference in the outcome, it is not because of

Observational studies

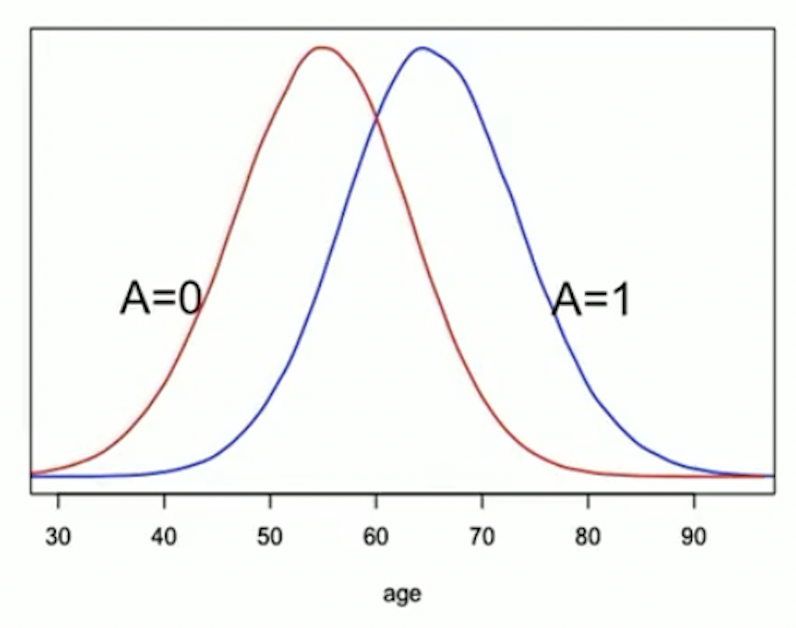

In observational studies, the distribution of may differ between treatment groups

For example, older people may be more likely to get treatment :

Overview of matching

Matching

Matching: a method that attempts to make an observational study more like a randomized trial

Main idea of matching: match individuals in the treated group to individuals in the control group on the covariates

- Usually, the sample size of the treated group is smaller than the control group, so after matching, we will use all cases in the treated group, but only a fraction of the cases in the control group

In the example where older people are more likely to get

- At younger (older) ages, there are more people with ()

In a randomized trial, for any particular age, there should be about the same number of treated and untreated people

This balance can be achieved by matching treated people to control people of the same age

Advantages of matching

Controlling for confounders is achieved at the design phase, i.e., without looking at the outcome

Matching will reveal lack of overlap in covariate distribution

- Positivity assumption will hold in the population that can be matched

We can treated a matched dataset as if from a randomized trial

Outcome analysis is simple

Match on a single covariate

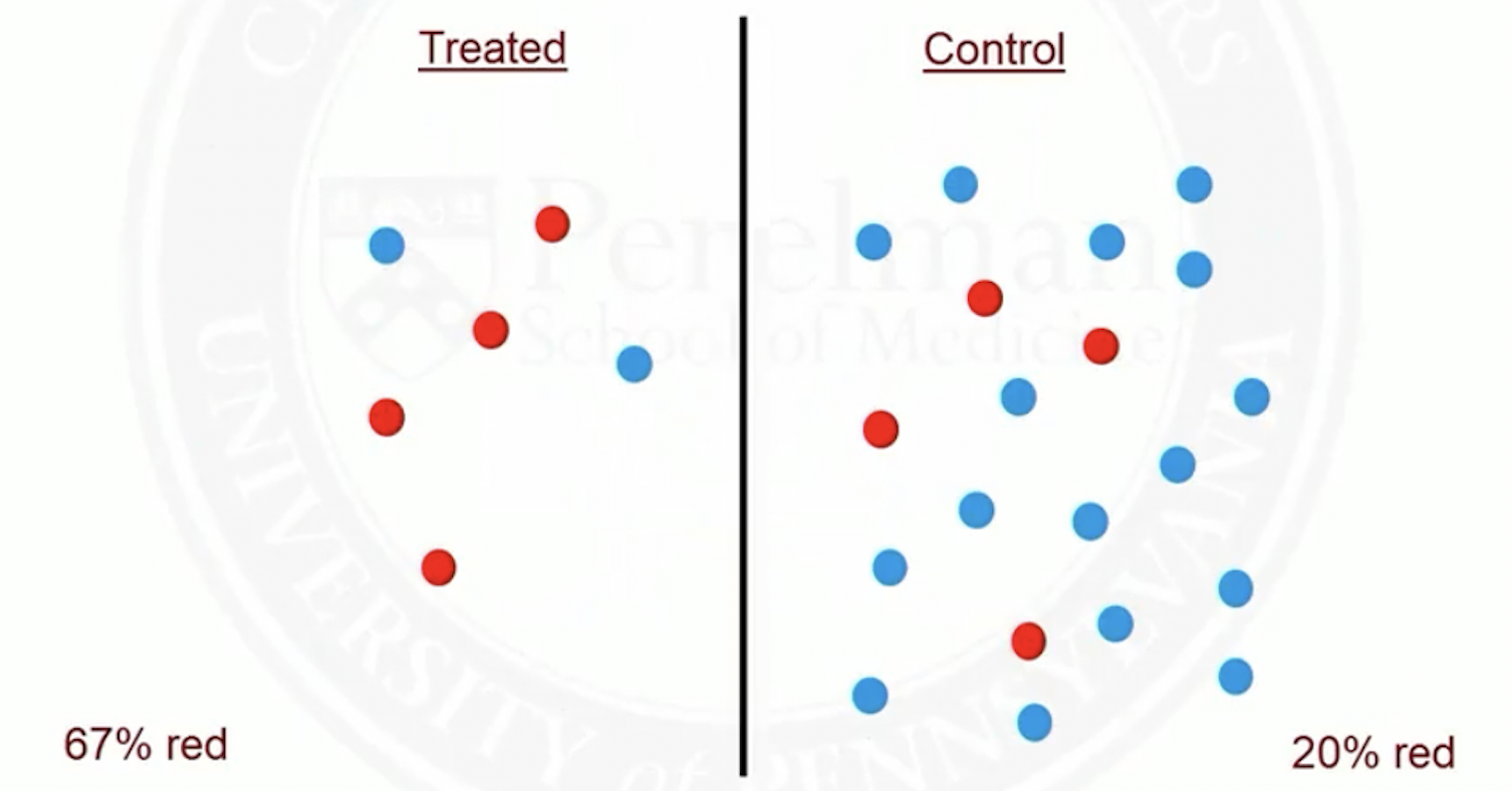

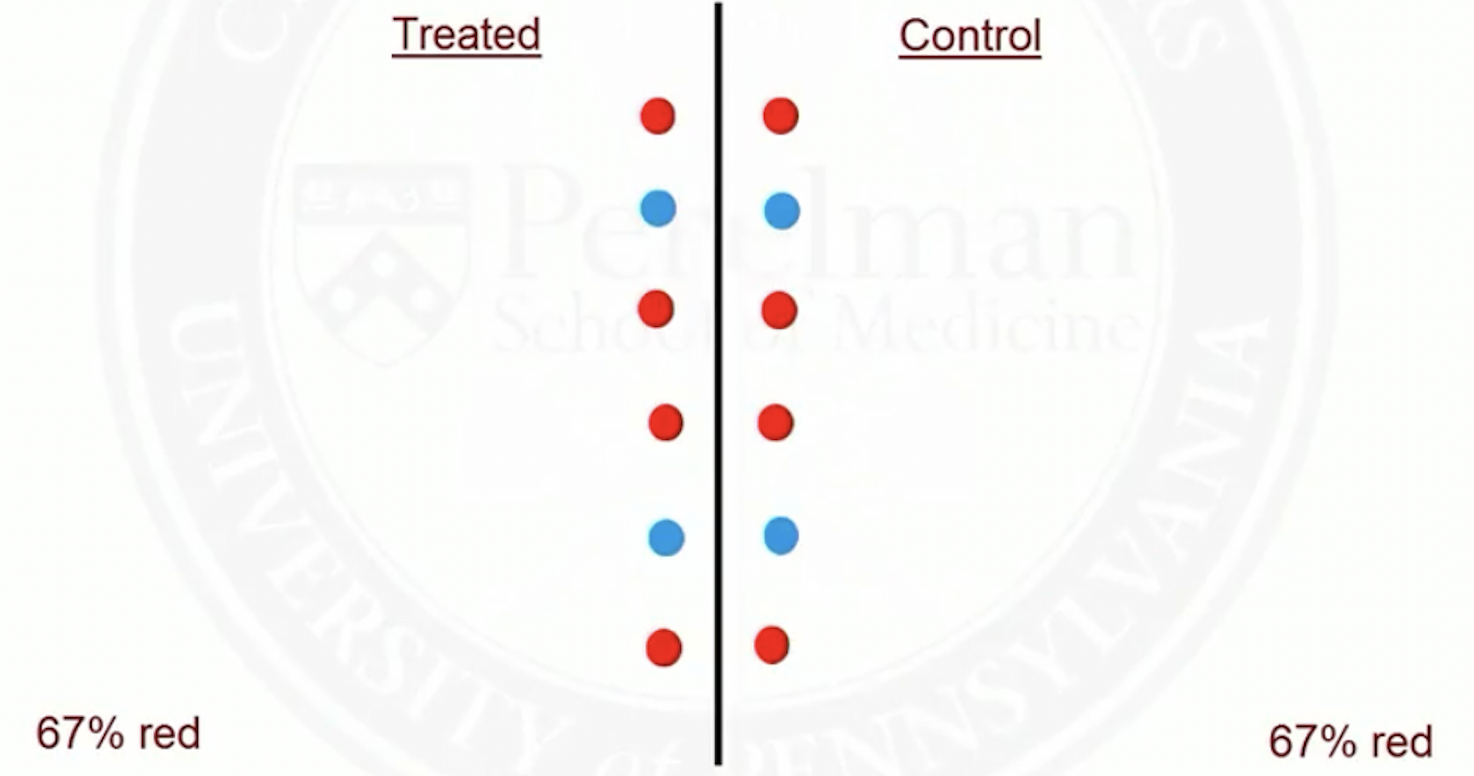

Suppose red patients are more likely to be treated than blue ones

Before matching

- After matching

Match on many covariates

We will not be able to exactly match on the full set of covariates

In randomized trials, treated and control subjects are not perfect matches either; the distribution of covariates is balanced between groups (stochastic balance)

Matching closely on covariates can achieve stochastic balance

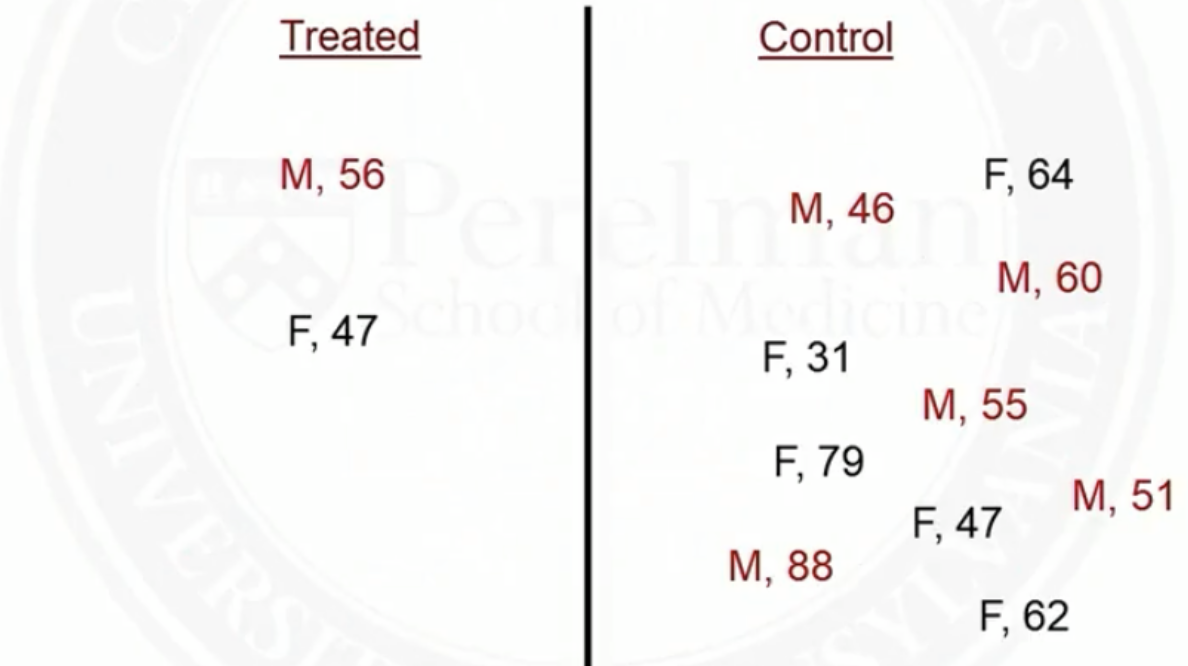

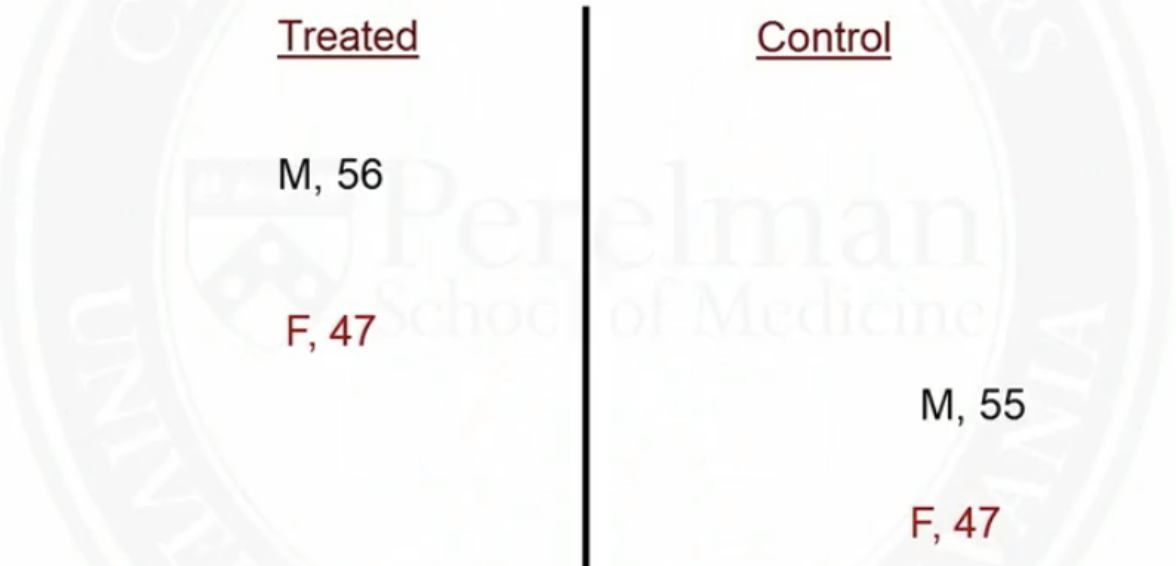

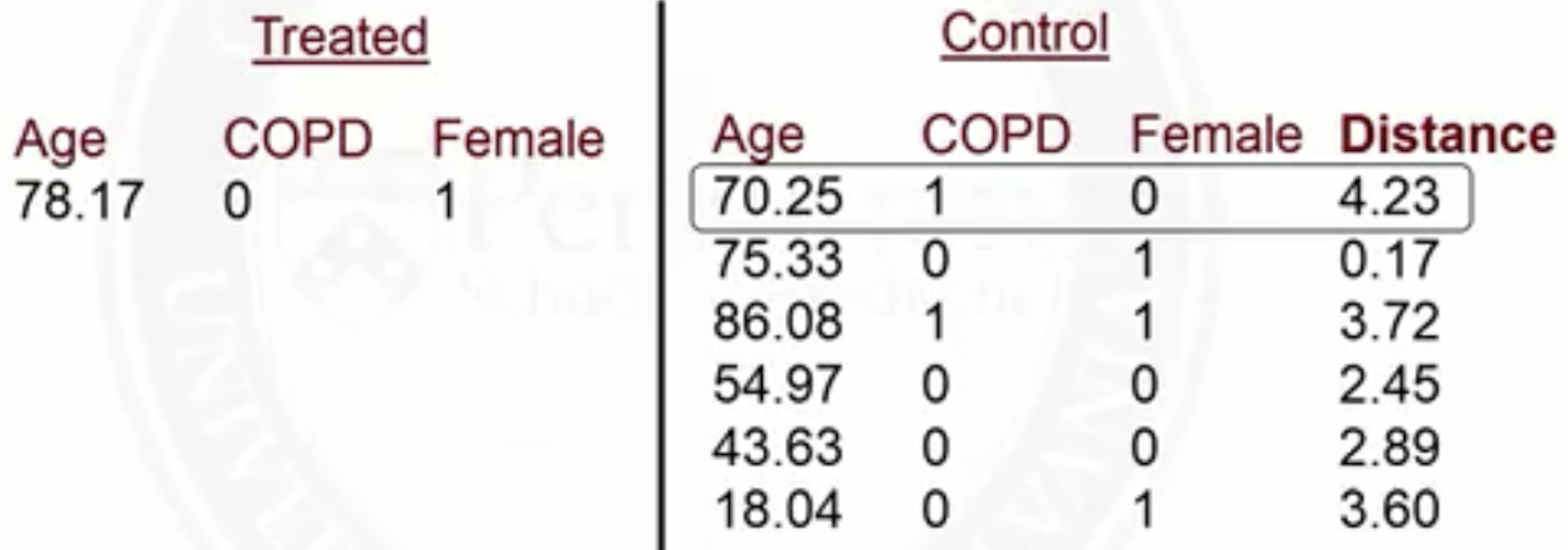

Example of matching on two covariates: sex and age

- Before matching

- After matching

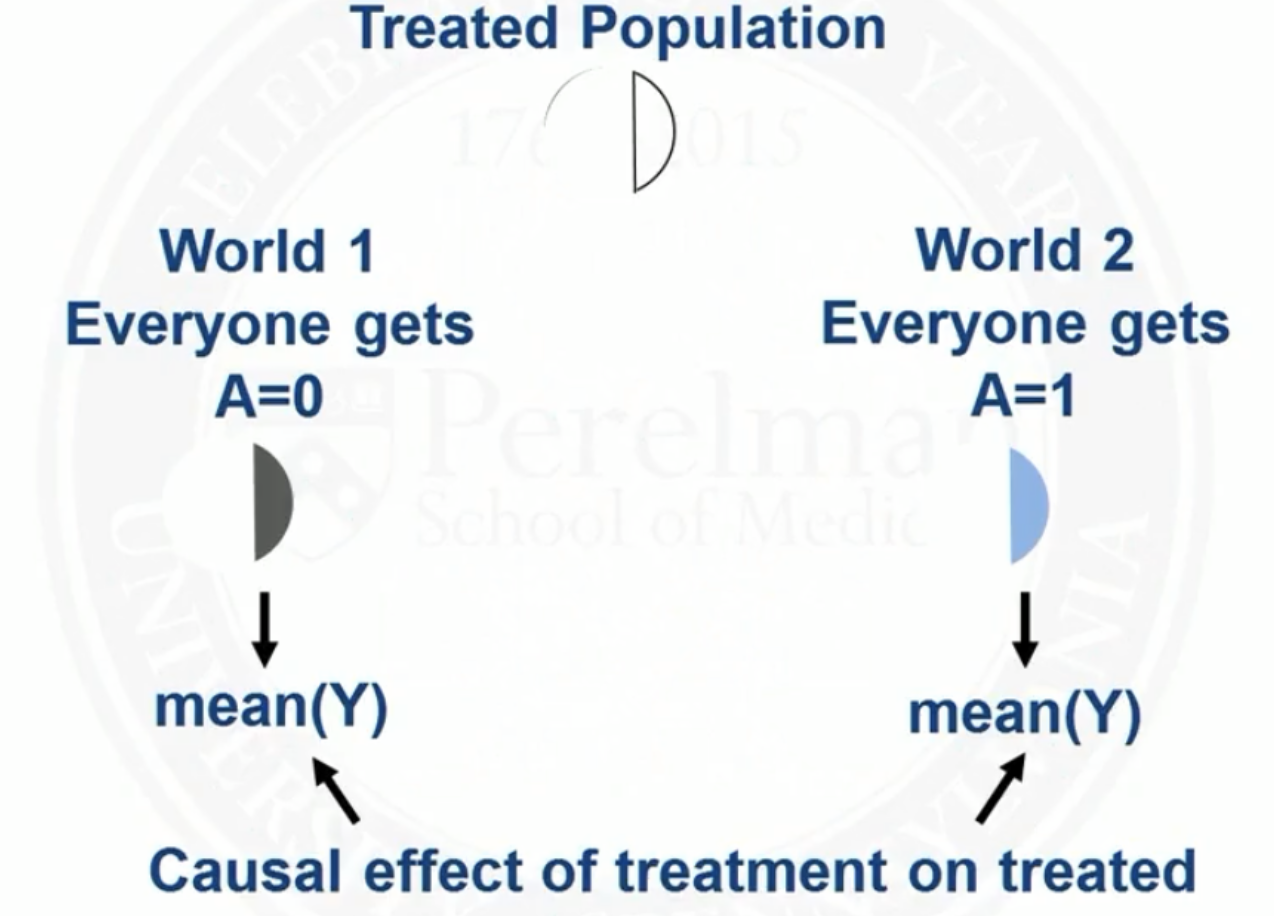

Target population of matching: the treated

By matching, we are making the distribution of covariates in the control population look like that in the treated population

So we will analysis causal effect of treatment on the treated

- There are matching methods that can be used to target a different population (beyond scope of this course)

Fine balance

Sometimes it is hard to find great matches, so we are willing to accept some non-ideal matches, if treated and control groups have the same distribution of covariates (fine balance)

For the matches below, average age and percent female are the same in both groups, although neither match is great

- Match 1: treated, male, age 40 and control, female, age 45

- Match 2: treated, female, age 45 and control, male, age 40

Number of matches

One to one (pair matching): match one control to every treated subject

Many to one: match (a fixed number) controls to every treated subject; e.g., 5 to 1 matching

Variable: sometime match 1, sometimes more than 1 (if multiple good matches available), control to treated subjects

Metrics used in matching

Mahalanobis distance between two vectors:

- We use covariance to scale so that the M distance is invariant of unit change

Robust Mahalanobis distance: robust to outliers

- Replace each covariate value with its rank

- Constant diagonal on covariance matrix

- Calculate the usual M distance on the ranks

Types of matching

- Greedy (nearest neighbor) matching

- Not ideal, but computationally fast

- Optimal matching

- Better, but computationally demanding

Nearest neighbor matching

Setup

We have selected a set of pre-treatment covariates that satisfy the ignorability assumption

We have calculated a distance between each treated subject and each control subject

We have more control subjects than the treated subjects

We will focus on pair matching (one-to-one)

Nearest neighbor matching (greedy)

Randomly order list of treated subjects and control subjects

Start with the first treated subject, match to the control with the smallest distance

Remove the matched control from the list of available matches

Move on to the next treated subject. Repeat until all treated subjects are matched

Not invariant to order initial order of list

Not optimal: always taking the smallest distance match does not minimize total distance

R package: MatchIt, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MatchIt/MatchIt.pdf

Many-to-one matching

For :1 matching: after everyone has 1 match, go through the list again and find 2nd matches. Repeat until matches

Pair matching (one-to-one) vs many-to-one matching: a bias-variance tradeoff

Pair matching: closer matches, faster computing time

Many-to-one matching: larger sample size

Caliper

We may exclude a treated subject if there is no good matches for it

Caliper: maximum acceptable distance

- Only match a treated subject if the best match has distance less than the caliper

If no matches within caliper, it is a sign of violation of the positivity assumption. So we should exclude these subjects

Drawback: population harder to define

Optimal matching

Optimal matching

Optimal matching: minimized global distance measure, e.g., total distance

Computational feasibility of optimal matching: depends on the size of the problem

Number of treatment-control pairing: product of number of treatment and number of control

1 million treatment-control pairings is feasible on most computers (not quick, though)

1 billion pairings is not feasible

R packages: optmatch, rcbalance

Assessing matching balance

Assessing matching balance

- Check covariate balance: compute standardized difference to see if each covariate has similar means between treatment and control

- Does not depend on sample size

- Often, absolute value of smd is reported

- We calculate smd for each variable we match on

- This analysis does not involve the outcome variable

Rule of thumb:

- : adequate balance

- : not too alarming

- : serious imbalance

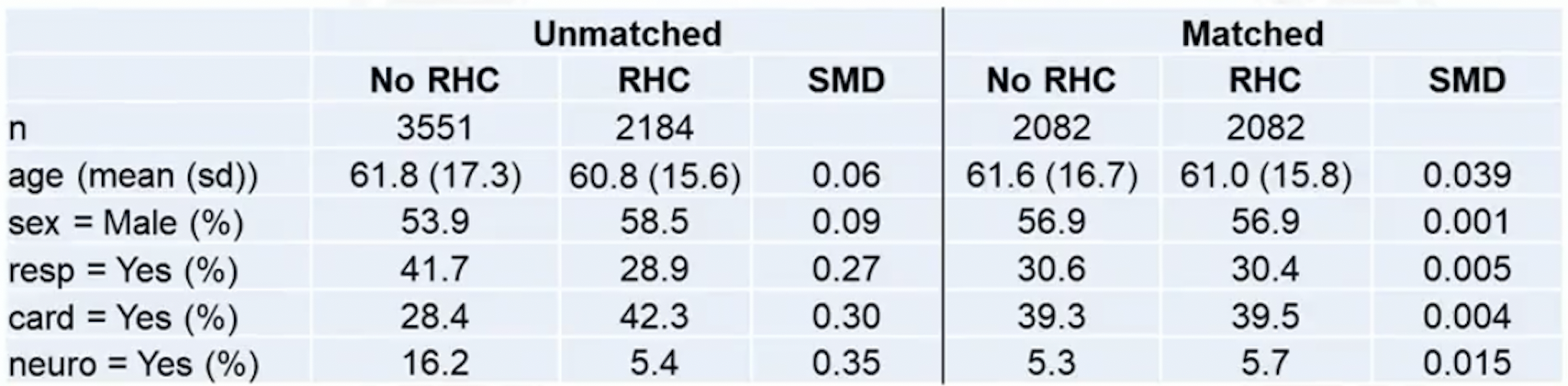

Example: right heat characterization (RHC) data

- Table 1: compares pre-matching and post-matching balance

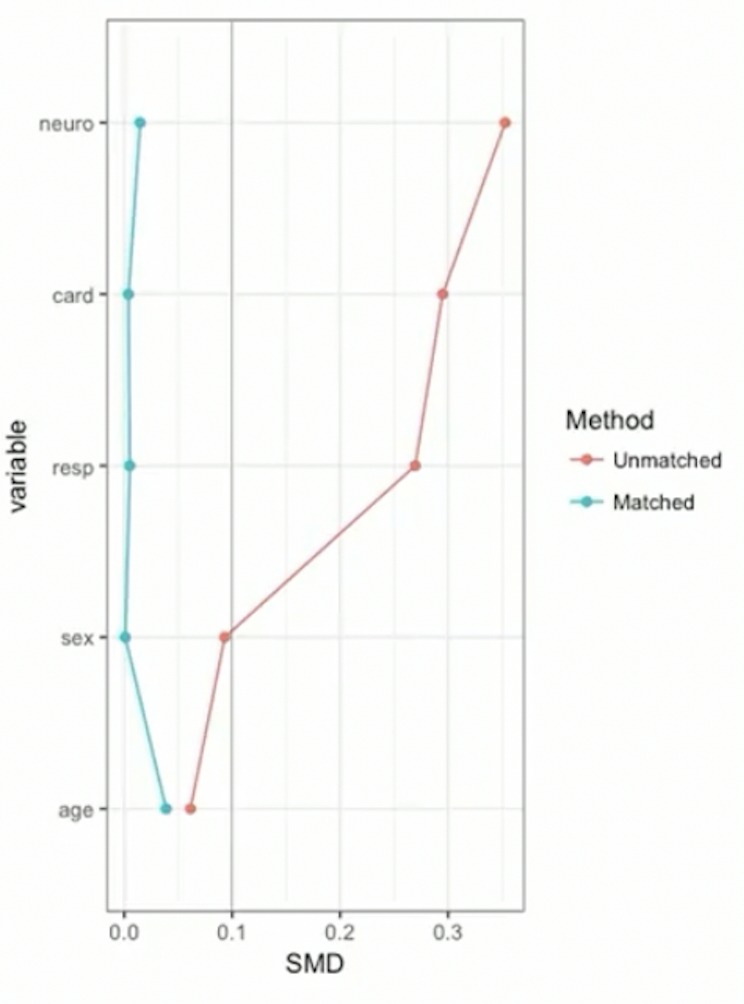

Example continued: RHC data

- SMD plot: visualizes Table 1

Analyze data after matching

After matching, proceed with outcome analysis

Test for a treatment effect

Estimate a treatment effect and confidence interval

Methods should take matching into account

Randomization test

Also known as permutation tests or exact tests

Main ideas of randomization test

Compute test statistic from observed data, assuming null hypothesis of no treatment effect is true

Randomly permute treatment assignment within pairs and recompute test statistic

Repeat many times and see how unusual observed statistic is

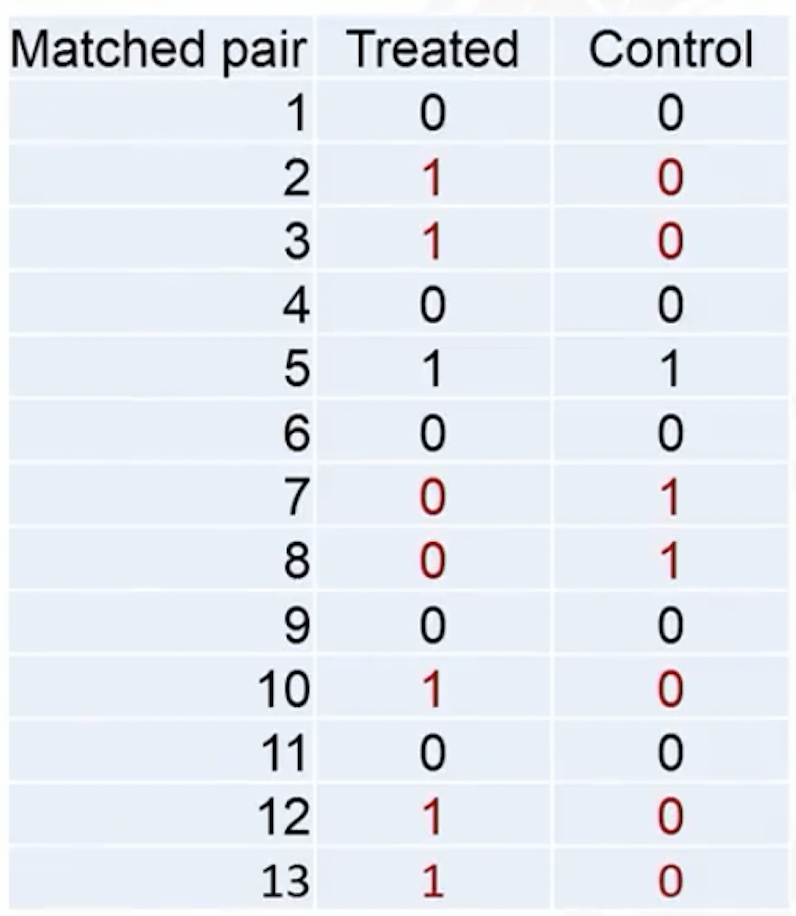

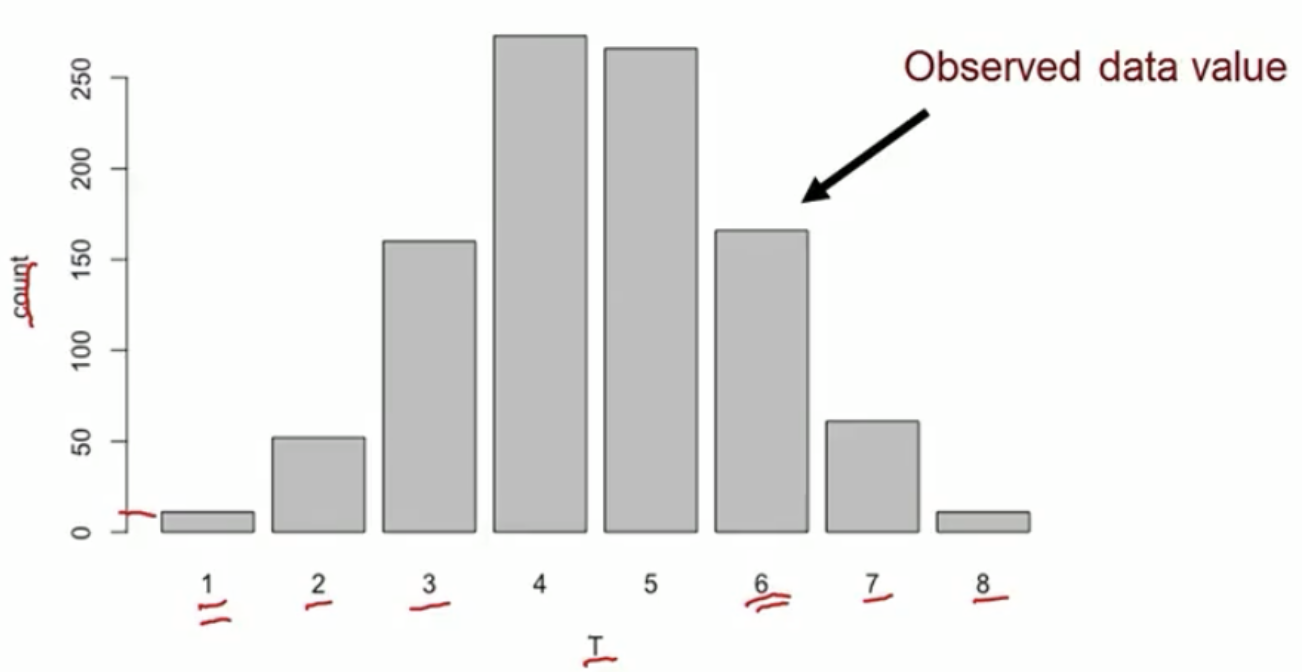

A binary outcome example

Test statistic: the total number of events in the treated group

- Test stat in the observed data

- In the observed data, discordant pairs (in red) are the only ones can change during treatment permutation

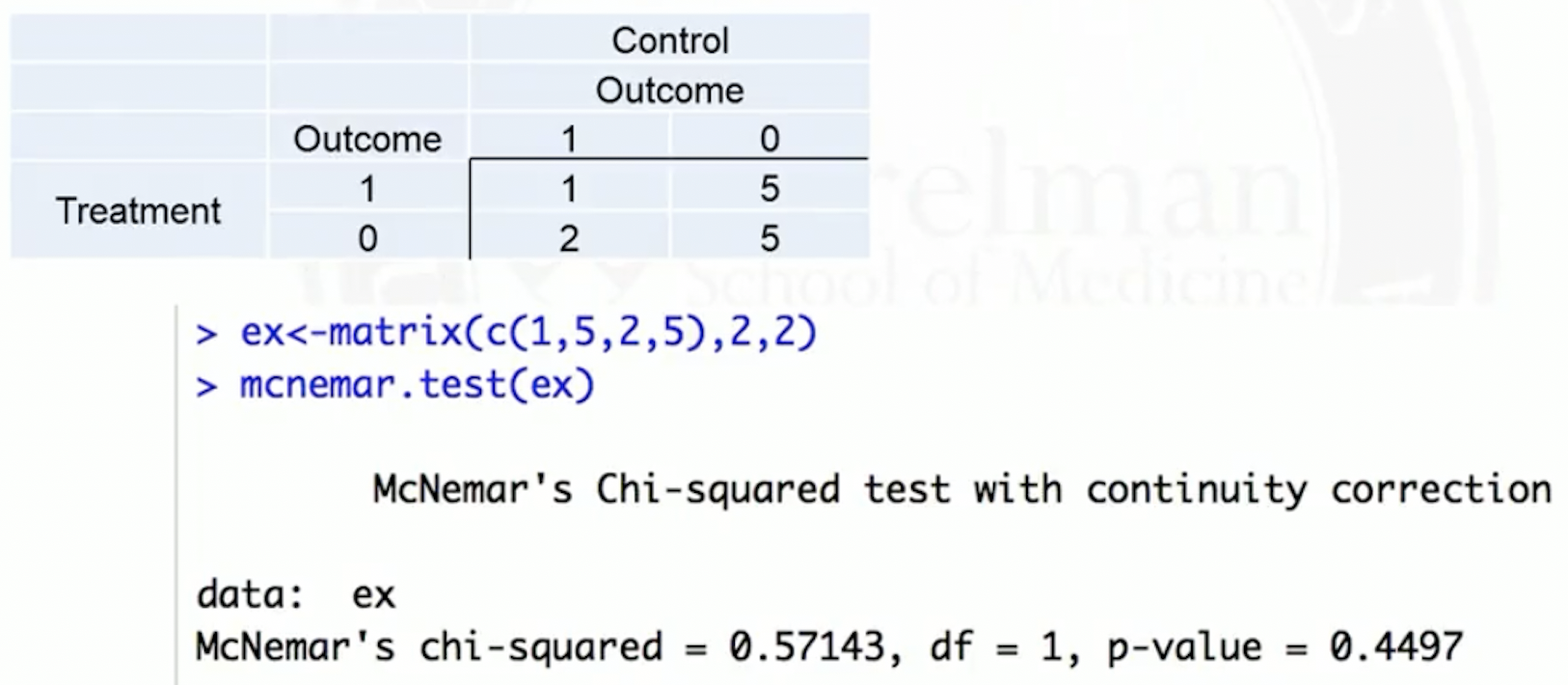

Permutation test for binary outcome: equivalent to a NcNemar test

NcNemar test: whether row and column marginal frequencies are the same, for paired binary data

- Paired binary data, represented in a 2 by 2 contingency table

| Test 2 positive | Test 2 negative | Row total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1 positive | |||

| Test 1 negative | |||

| Column total |

Hypotheses: whether , or equivalently,

Test statistic

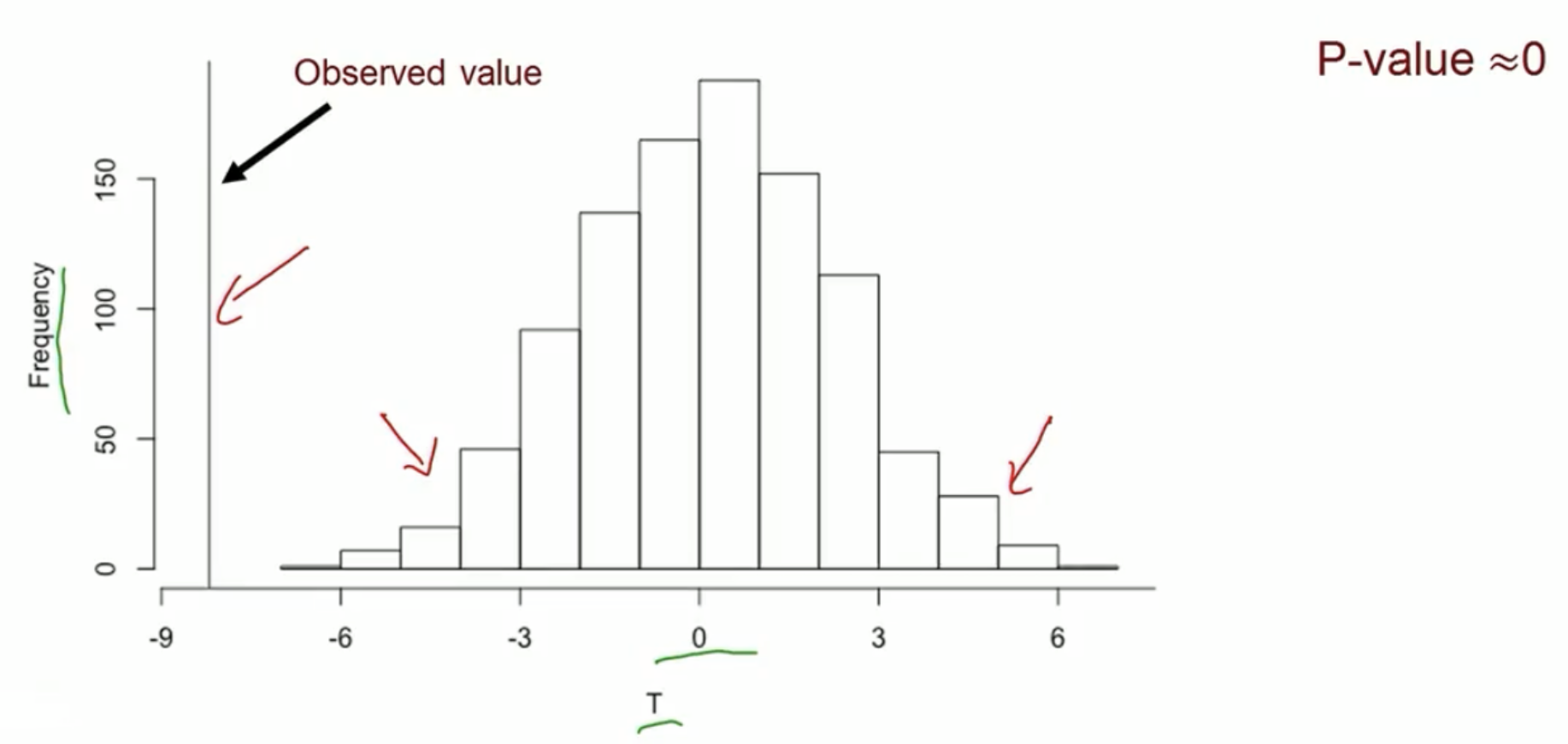

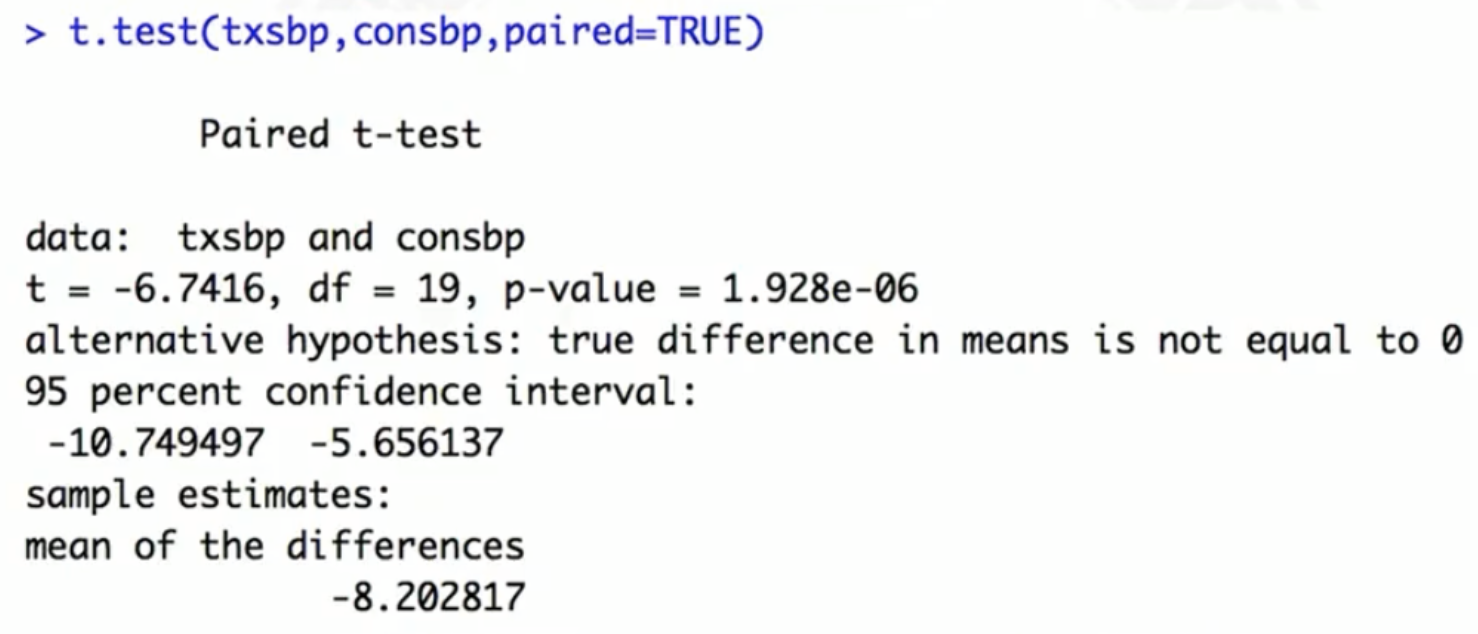

Permutation test for continuous outcome: equivalent to a paired t-test

- Test statistic: difference in sample means

Other outcome models

Conditional logistic regression

- Matched binary outcome data

Generalized estimating equations (GEE)

- Match ID variable used to specify clusters

- For binary outcomes, can estimate a causal risk difference, causal risk ratio, or causal odds ratio (depending on link function)

Propensity Score

Propensity score

Propensity score: probability of receiving treatment, given covariates

Propensity score is a balancing score

- Suppose two subjects have the same value of propensity score, but different covariate values

- This means that both subjects’ is just as likely to be found in the treatment group

- So if we restrict to a subpopulation of subjects who have the same value of the propensity score, there should be balance in the treatment vs control groups

We can match on propensity score to achieve balance

Logistic regression to estimate propensity score

In a randomized trial, the propensity score is known

In an observational study, we need to estimate the propensity score

- Fit a logistic regression: outcome , covariates

- Get the predicted probability (fitted value) for each subject as the estimated propensity score

Propensity score matching

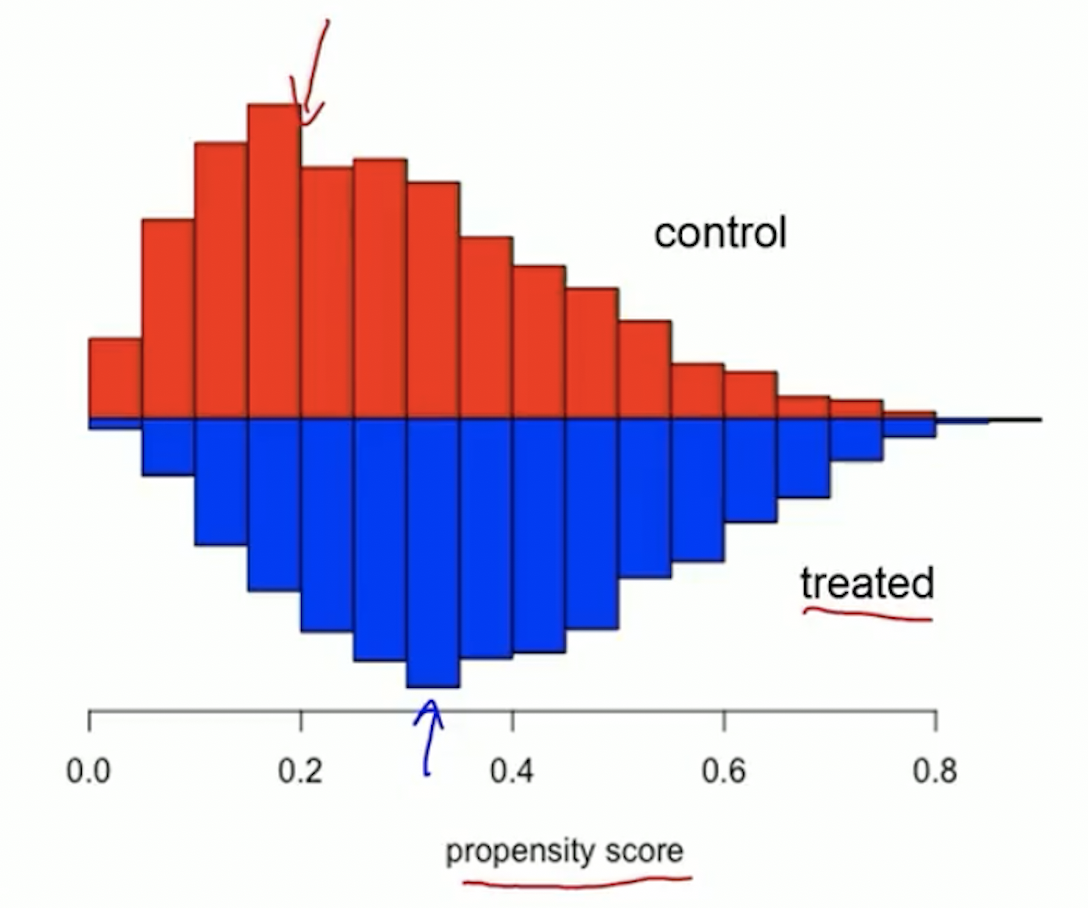

Before propensity score matching: check for overlap

Propensity score matching is simple; it’s matching on one variable

After the propensity is estimated, but before matching, it is useful to look for overlap

- This is to check positivity assumption

Example of good overlap

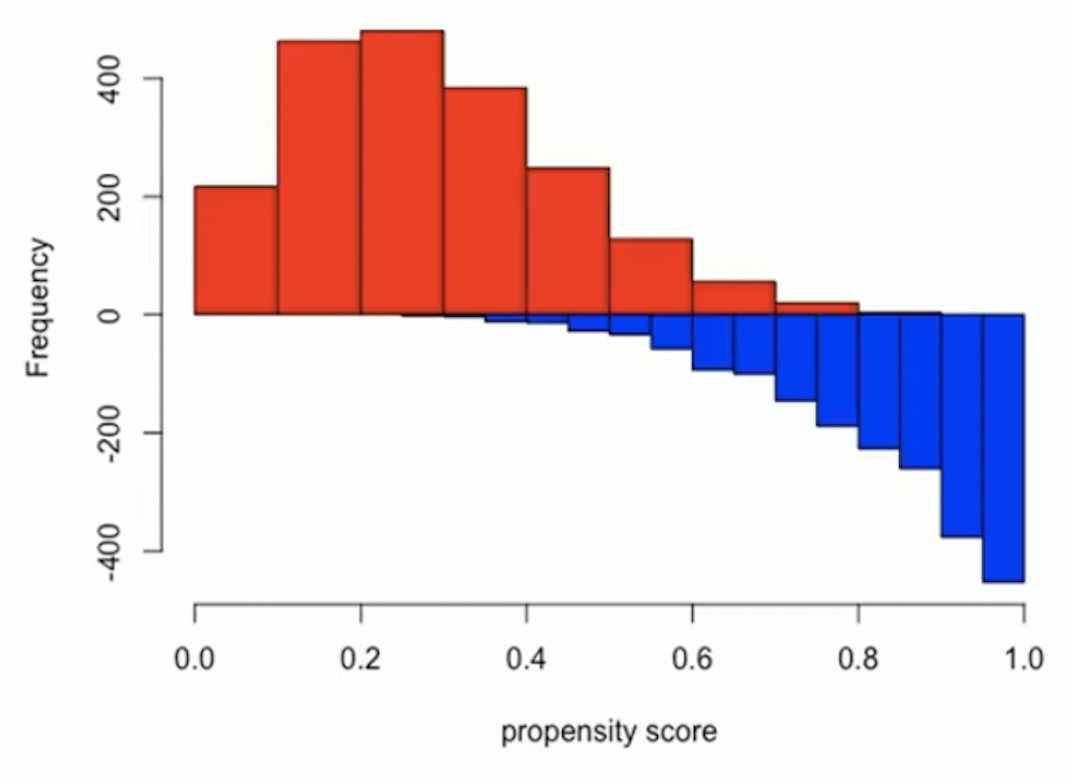

Trim tails if there is a lack of overlap

- Example of bad overlap

Trim tails: remove subjects who have extreme values of propensity score

- Remove control subjects whose propensity score is less than the minimum in the treatment group

- Remove treated subjects whose propensity score is greater than the maximum in the control group

Propensity score matching

Compute a distrance between the propensity score for each treated subject with every control

Use nearest neighbor or optimal matching

In practice, logit of the propensity score is often used, rather than the propensity score itself

A caliper can be used to avoid bad matches

- After matching: outcome analysis

- Randomization tests

- Conditional logistic regression, GEE, etc

References

Coursera class: “A Crash Course on Causality: Inferring Causal Effects from Observational Data”, by Jason A. Roy (University of Pennsylvania)